NextGenRadio

Oklahoma

Finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation.

Centennial of the

1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

A collection of audio and digital stories highlighting the experiences of people in the 100-year aftermath of what is believed to be the single worst incident of racial violence in American history.

This project was produced in April 2021 in partnership with Oklahoma State University School of Media and Strategic Communications and KOSU. Our reporters are students in Oklahoma.

An Oklahoma State University professor is inputting data into a mapping program to show how the Tulsa Race Massacre transformed the neighborhood throughout the years.

Illustration by Emily Whang

Mapping Tulsa’s Greenwood District back to life

Sean Thomas spends several hours a day working on a map that shows where most of the homes and businesses were located in the Greenwood District before the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre up until today. Through his map, he hopes to help people feel a “kind of tie to the space and strengthen that collective identity to Greenwood.”

Thomas is a Ph.D student in the geography department of Oklahoma State University and also teaches cultural geography there. Despite growing up in Oklahoma City and living in the state his entire life, he hadn’t learned anything about the massacre until he was in his 20s. After he heard airplanes had been used to drop bombs on civilians, he decided to look deeper into what happened.

“At first I was a bit taken aback by the fact that I had never heard of it before,” Thomas said. “I’ve read probably six books about the Tulsa Race Massacre now.”

LISTEN TO THE STORY

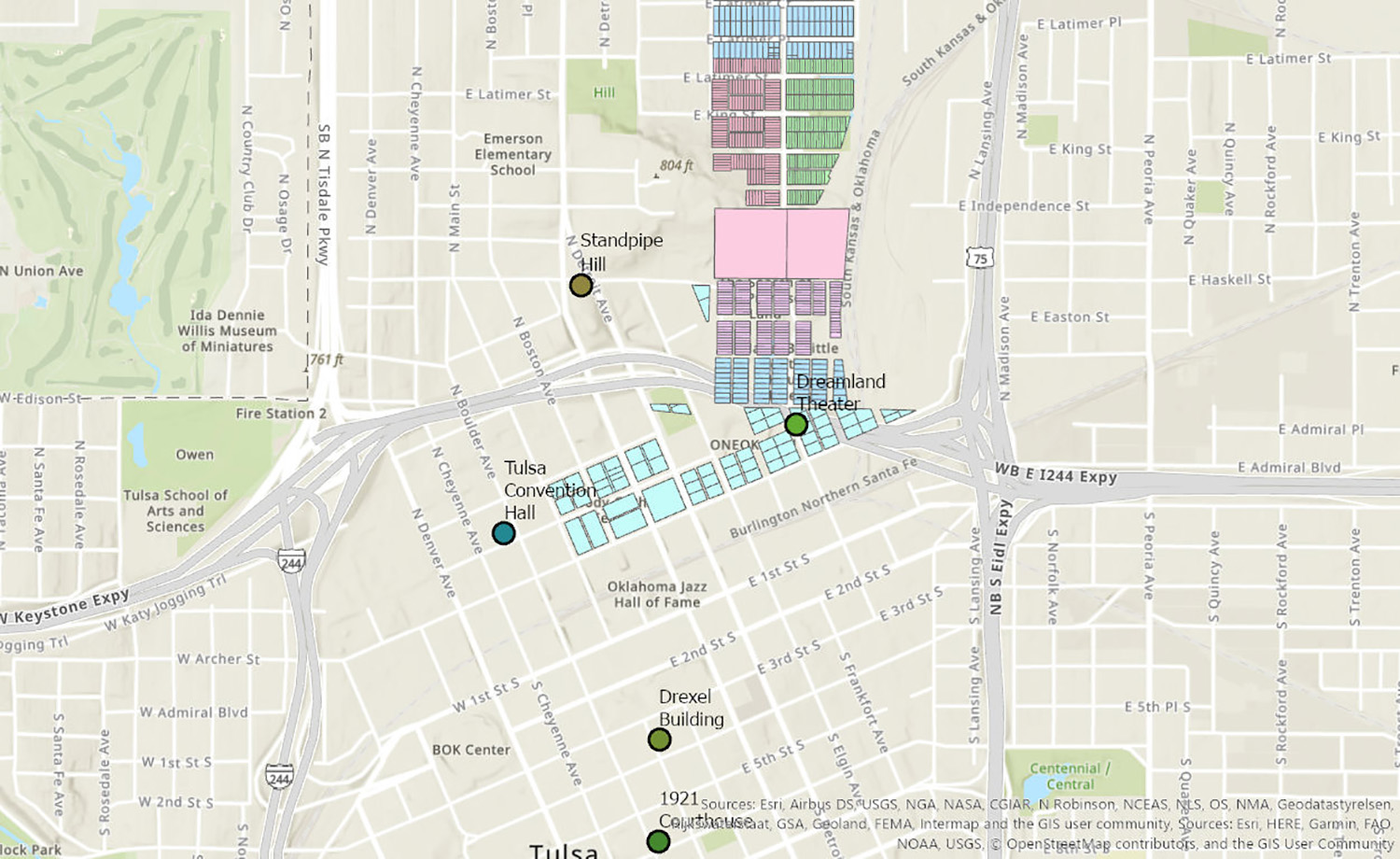

Thomas got inspired to start mapping the Greenwood area. In his map, you can see the official city property lines for each of the blocks. Each plot of land is color-coded and labeled to show who owned the property at the time. The map shows Deep Greenwood, or Black Wall Street; the Vernon AME Church, a landmark that withstood the bombings; and the Dreamland Theatre, the first movie theater in Tulsa that Black people could go to.

To put together the map, he collected 600 handwritten pages of old property ownership data.

“They’re all handwritten with really bad handwriting,” he said. “And that has to be entered one at a time into an Excel sheet. I have actually had to enlist the help of my wife with that one, because I get frustrated trying to read that handwriting.”

He said they typically work just a few hours a day “to maintain sanity.”

Oklahoma State University Professor Sean Thomas has been working on a map of the Greenwood District since May. Data from the map will go into an app, so people can walk around the neighborhood and see who owned the properties. (Map courtesy of Sean Thomas)

On top of that, Thomas is taking all the data for the map and developing an app so people can access the information from anywhere.

Thomas hopes that when he finishes mapping Greenwood, he’ll be able to share it with his students. His plan is to get the app polished and then give it to Greenwood Rising, a history museum, so it’s available for visitors who want to tour the neighborhood. That way, he said, they can “feel more of that connection to their space through a historical connection with family members.”

“If someone is a descendent of a survivor of Greenwood, they can have this map and they can walk around and say, ‘Oh, my great grandfather owned this property in 1921 or 1931.’”

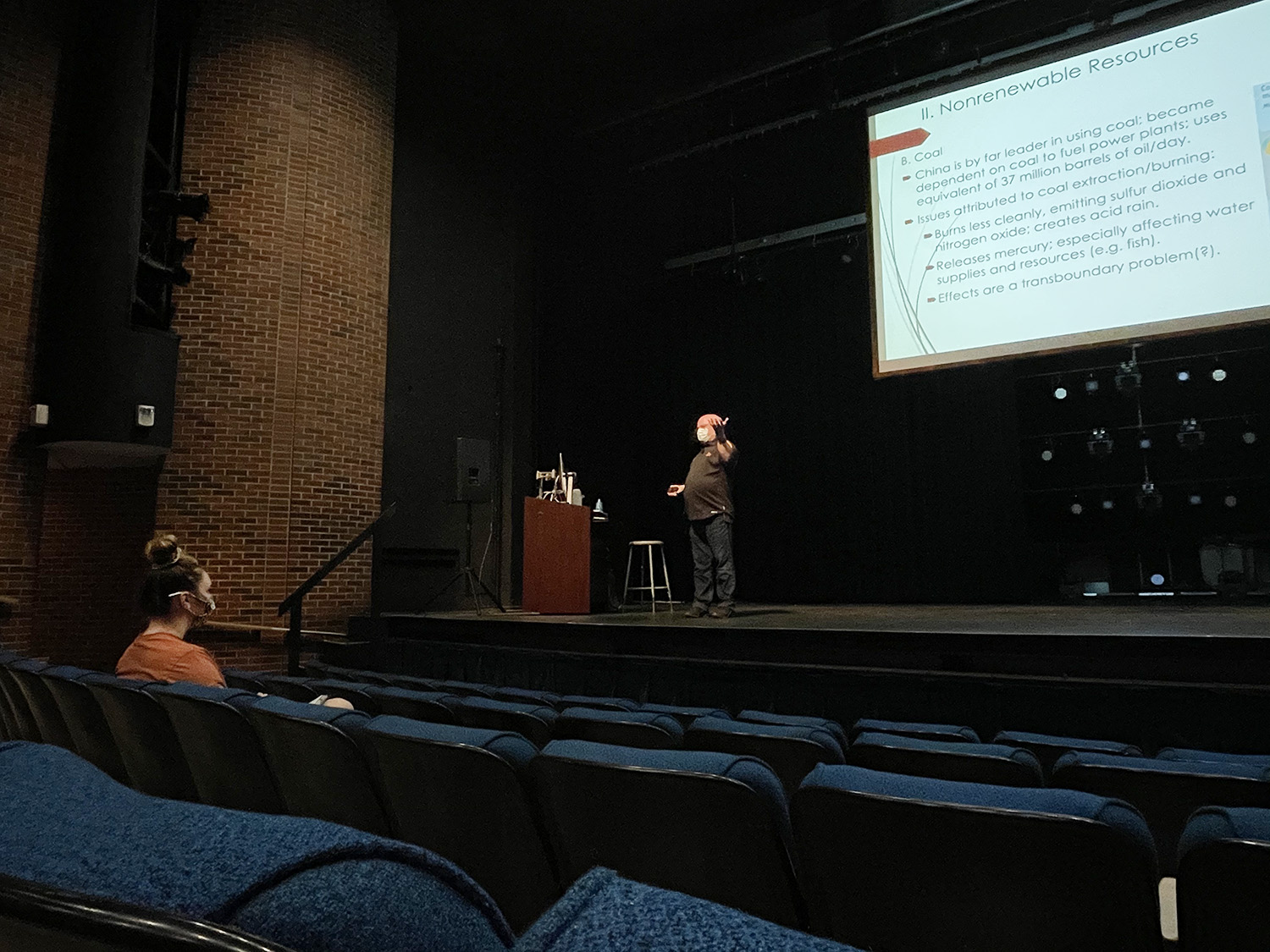

Thomas teaches cultural geography at OSU and covers racial issues in his class. He hopes one day he will be able to share the map with his students. (Photo by Rodrigo Solis Ruiz)