NextGenRadio

Oklahoma

Finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation.

Centennial of the

1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

A collection of audio and digital stories highlighting the experiences of people in the 100-year aftermath of what is believed to be the single worst incident of racial violence in American history.

This project was produced in April 2021 in partnership with Oklahoma State University School of Media and Strategic Communications and KOSU. Our reporters are students in Oklahoma.

Carlos Moreno moved to Tulsa from California over 20 years ago, and through his work discovered a treasure trove of storytellers and information. Now, one hundred years after the Tulsa Race Massacre, Moreno has catalogued those stories for a book to be released coinciding with the commemoration. We spoke about how his journey of learning about the community changed his perception of Black Wall Street, the events leading up to the Tulsa Race Massacre and his thoughts on Greenwood today.

Illustration by Ard Su

Looking at Greenwood with our hearts, not minds: Tulsa resident finds treasure in descendants and documents

“When I discovered everything that I discovered, it was like opening a treasure chest,” Carlos Moreno said. “There would be a little piece in one book and another little piece in another book and when you put all these pieces together, you get this picture of a very rich life that this person lived.”

When Moreno, a graphic designer and community activist, moved to Tulsa from San Jose, Calif., in 1998, he never imagined he’d be sharing stories from the Greenwood elders more than 20 years later.

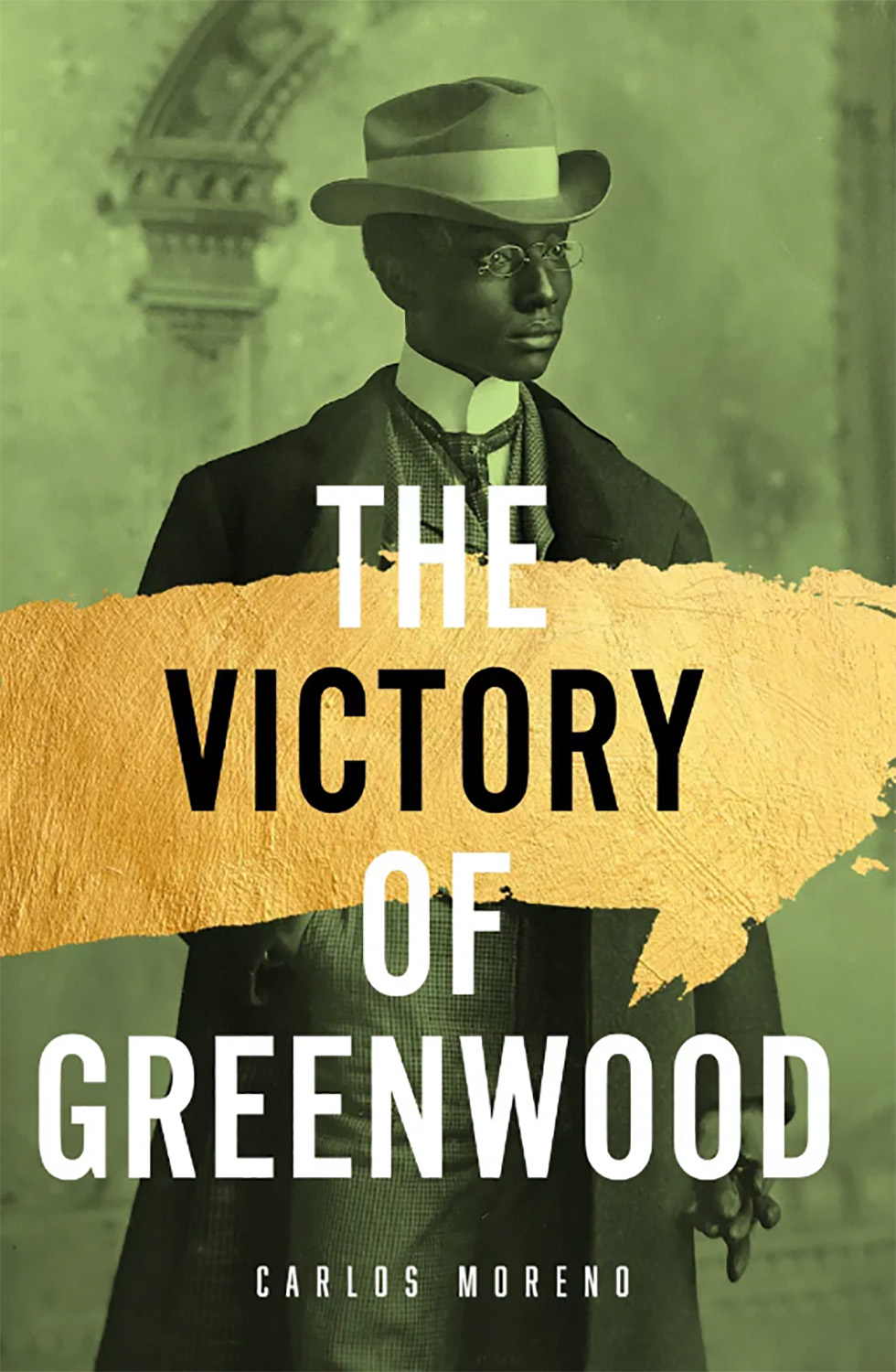

With his first book “The Victory Of Greenwood” premiering in the year of the Tulsa Race Massacre centennial, Moreno’s hope is that those who read it grasp that the victims were real people.

His journey to learning the real history of Greenwood and the events leading to the massacre began in the early 2000s while he was freelancing for The Oklahoma Eagle, the oldest Black newspaper in Tulsa and the first Black daily newspaper in the country.

LISTEN TO THE STORY

“They wanted to create, kind of, a special issue of the newspaper where people could really understand about the massacre and about the history of Greenwood,” Moreno said. “I kind of didn’t know at that time how valuable an experience that really was until much later.”

While he was working on graphics for the special issue, Moreno was also learning about the history from descendants of those who were impacted by the Tulsa Race Massacre.

At the same time, Moreno began working with Don Ross, a former Oklahoma State Senator on his computers. Ross helped bring the previously hidden events of the violence to light in the 1970s — despite attempts to suppress and conceal important details — when he published an objective article about the massacre by historian Ed Wheeler in Impact Magazine in 1971.

“I can remember just hearing stories from people like Don Ross,” Moreno said. “He didn’t trust computer stores or our computer repair shops, so any time his computer would break down, he would just call me. The whole time I’m there…what do you have to do, but just tell me stories?”

Those conversations are what led Moreno to developing relationships with other direct descendants of the massacre. Through his journey and conversations with the people of Greenwood, Moreno discovered not only was the mob violence kept hidden, but the accomplishments and resilience of the community was concealed as well.

As a result, his understanding of the district and the massacre evolved from a curiosity about what happened to a passion to tell the victims’ stories from the most accurate lens possible.

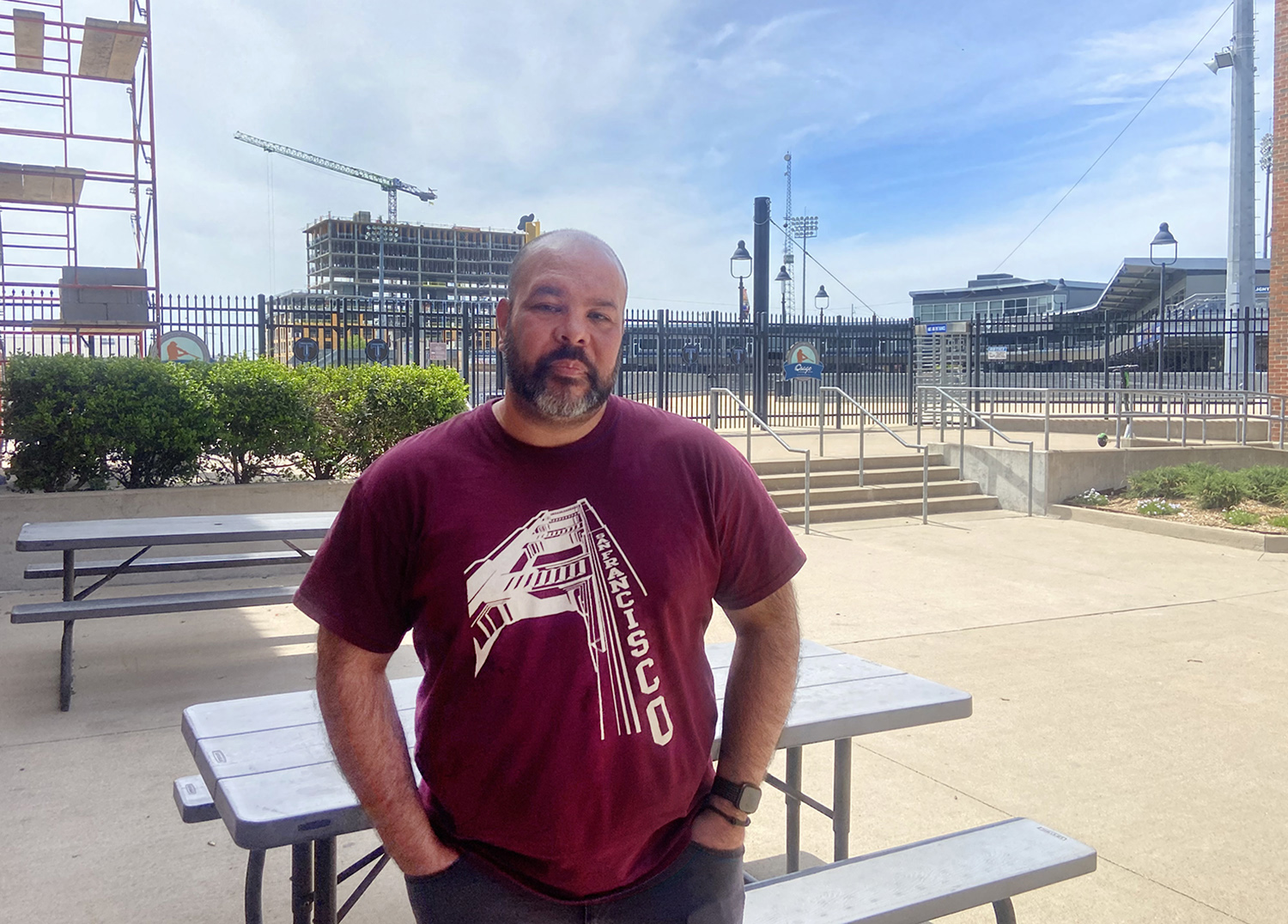

Carlos Moreno stands at the entrance to ONEOK Field baseball park in Greenwood district, with more new construction in the background. Both structures were considered controversial by the citizens of Greenwood. (Photo by Crystal Patrick)

By bringing stories of Greenwood founders like O.W. Gurley, John and Lulu Williams to life in his book of biographies, The Victory of Greenwood, readers can learn, as Moreno did, from first-hand accounts of people who experienced the massacre and their descendants, not a textbook.

“The current narrative we have is just completely wrong, you know, and so it just really got to me so much that people weren’t looking through the same lens that I had learned about Greenwood from and that people weren’t digging into the primary documents to learn the real history,” Moreno said.

One of Moreno’s biggest takeaways was that for the people who had heard about the Greenwood massacre, the context surrounding the violence was omitted.

Moreno came to the conclusion that the theft of Greenwood started in 1921 and has continued to this day. The first theft was the massacre, but after the rebuilding, another theft came with urban renewal. Moreno feels especially connected to this story because his childhood neighborhood in San Jose also suffered the effects that many Black and brown communities did with the Federal Aid Highway Act; their businesses and homes were lost due to imminent domain.

“I think the thing that’s kind of most missing from the conversation about Greenwood and about the centennial is that the massacre wasn’t just an isolated event,” Moreno said. “It was planned beforehand… the city tried to prevent Greenwood from rebuilding afterwards. And Greenwood is still getting destroyed today by building all these new buildings.”

Although the structures of Greenwood were destroyed, the community rebuilt; it wasn’t completely decimated as the common narrative implies. Citizens, without local or federal aid, not only rebuilt Greenwood, but expanded greater than the area terrorized in 1921.

The buildings there now stand as a testimony of Greenwood’s resilience despite Highway I-244, built in 1967, which cuts the original historic 40 blocks of Greenwood in half. Today, placards built into the sidewalks line what was once Black Wall Street identifying businesses from the time of the massacre and whether or not they were rebuilt afterwards. The new buildings around the historic district seem far removed from the Black economic engine that Greenwood once was.

“At what cost and at what expense and who gets to decide Greenwood’s fate and its future?” Carlos said. “I don’t see it being the people of Greenwood, so these are difficult conversations that I don’t think Tulsa is ready to have yet.”

To coincide with the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre, Moreno is releasing his book of biographies, “The Victory of Greenwood.”

“I want to help people connect to Greenwood more with their hearts than with their minds,” Moreno said.

(Photo courtesy of Carlos Moreno )

This metal placard on the sidewalk reads: “Black Wall Street 1921- Meeks Building 102 North Greenwood. Destroyed 1921. Reopened.” Placards in the sidewalks identify businesses from the time of the massacre and whether or not they were rebuilt afterwards. (Photo by Crystal Patrick)

Buildings that were reconstructed after the bombing of Greenwood line the street. Scorched bricks from the massacre were used in the reconstruction of 108 N. Greenwood as a reminder of the violence that happened one hundred years ago. (Photo by Crystal Patrick)